Review by: Donald Prothero, PhD

In everything the prudent acts with knowledge, but a fool flaunts his folly.—Proverbs 13:16Ignorance more frequently begets confidence than does knowledge.—Charles Darwin, The Descent of ManThe fool doth think he is wise, but the wise man knows himself to be a fool.—William Shakespeare, As You Like It

The Dunning-Kruger effect is a well-known phenomenon in psychology first named in 1998, but it has been recognized since before the Bible and Shakespeare. In a nutshell, it is (as Bertrand Russell put it)

”The trouble with the world is that the stupid are cocksure and the intelligent are full of doubt”. There is also another well-known psychological phenomenon: motivated reasoning. Our brains have many blind spots in them that allow us to reconcile the real world with the world as we want it to be, and reduce the clash of cognitive dissonance. The most familiar of these is confirmation bias, where we see only what we want to see, and ignore or forget anything that doesn’t fit our preferred world-view. When this bias emerges in argument, it takes the form of cherry-picking: finding a few facts out of context that seem to support what we want to believe, and ignoring everything else that contradicts what we are trying to promote.

The entire literature of creationism (and of its recent offspring, “intelligent design” creationism) works entirely on that principle: they don’t like any science that disagrees with their view of religion, so they pick tiny bits out of context that seem to support what they want to believe, and cherry-pick individual cases which fits their bias. In their writings, they are legendary for “quote-mining”: taking a quote out of context to mean the exact opposite of what the author clearly intended (sometimes unintentionally, but often deliberately and maliciously). They either cannot understand the scientific meaning of many fields from genetics to paleontology to geochronology, or their bias filters out all but tiny bits of a research subject that seems to comfort them, and they ignore all the rest.

Another common tactic of creationists is credential mongering. They love to flaunt their Ph.D.’s on their book covers, giving the uninitiated the impression that they are all-purpose experts in every topic. As anyone who has earned a Ph.D. knows, the opposite is true: the doctoral degree forces you to focus on one narrow research problem for a long time, so you tend to lose your breadth of training in other sciences. Nevertheless, they flaunt their doctorates in hydrology or biochemistry, then talk about paleontology or geochronology, subjects they have zero qualification to discuss. Their Ph.D. is only relevant in the field where they have specialized training. It’s comparable to asking a Ph.D. to fix your car or write a symphony—they may be smart, but they don’t have the appropriate specialized training to do a competent job based on their Ph.D. alone.

Stephen Meyer’s first demonstration of these biases was his atrociously incompetent book Signature in the Cell (2009, HarperOne), which was universally lambasted by molecular biologists as an amateurish effort by someone with no firsthand training or research experience in molecular biology. (Meyer’s Ph.D. is in history of science, and his undergrad degree is in geophysics, which give him absolutely no background to talk about molecular evolution). Undaunted by this debacle, Meyer now blunders into another field in which he has no research experience or advanced training: my own profession, paleontology. I can now report that he’s just as incompetent in my field as he was in molecular biology. Almost every page of this book is riddled by errors of fact or interpretation that could only result from someone writing in a subject way over his head, abetted by the creationist tendency to pluck facts out of context and get their meaning completely backwards. But as one of the few people in the entire creationist movement who has actually taken a few geology classes (but apparently no paleontology classes), he is their “expert” in this area, and is happy to mislead the creationist audience that knows no science at all with his slick but completely false understanding of the subject.

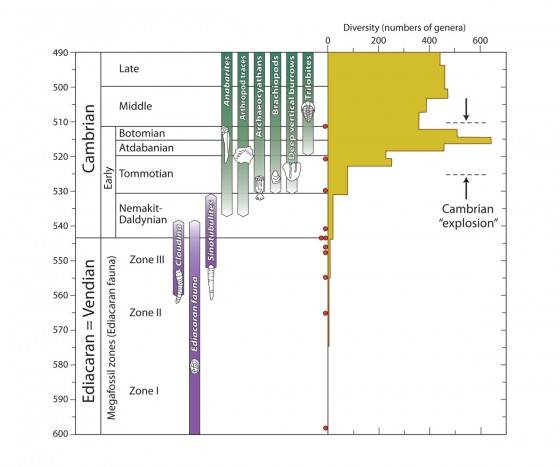

Let’s take the central subject of the book: the “Cambrian explosion”, or the apparently rapid diversification of life during the Cambrian Period, starting about 543 million years ago. When Darwin wrote about it in 1859, it was indeed a puzzle, since so little was known about the fossil record then. But as paleontologists have worked hard on the topic and learned a lot since about 1945 (as I discuss in detail in my 2007 book,Evolution: What the Fossils Say and Why it Matters). As a result, we now know that the “explosion” now takes place over an 80 m.y. time framework. Paleontologists are gradually abandoning the misleading and outdated term “Cambrian explosion” for a more accurate one, “Cambrian slow fuse” or “Cambrian diversification.” The entire diversification of life is now known to have gone through a number of distinct steps, from the first fossils of simple bacterial life 3.5 billion years old, to the first multicellular animals 700 m.y. ago (the Ediacara fauna), to the first evidence of skeletonized fossils (tiny fragments of small shells, nicknamed the “little shellies”) at the beginning of the Cambrian, 543 m.y. ago (the Nemakit-Daldynian and Tommotian stages of the Cambrian), to the third stage of the Cambrian (Atdabanian, 520-515 m.y. ago), when you find the first fossils of the larger animals with hard shells, such as trilobites. But does Meyer reflect this modern understanding of the subject? No! His figures (e.g., Figs. 2.5, 2.6, 3.8) portray the “explosion” as if it happened all at once, showing that he has paid no attention to the past 70 years of discoveries. He dismisses the Ediacara fauna as not clearly related to living phyla (a point that is still debated among paleontologists), but its very existence is fatal to the creationist falsehood that multicellular animals appeared all at once in the fossil record with no predecessors. Even more damning, Meyer completely ignores the existence of the first two stages of the Cambrian (nowhere are they even mentioned in the book, or the index) and talks about the Atdabanian stage as if it were the entire Cambrian all by itself. His misleading figures (e.g., Fig. 2.5, 2.6, 3.8) imply that there were no modern phyla in existence until the trilobites diversified in the Atdabanian. Sorry, but that’s a flat-out lie. Even a casual glance at any modern diagram of life’s diversification demonstrates that probable arthropods, cnidarians, and echinoderms are present in the Ediacara fauna, mollusks and sponges are well documented from the Nemakit-Daldynian Stage, and brachiopods and archaeocyathids appear in the Tommotian Stage—allmillions of years before Meyer’s incorrectly defined “Cambrian explosion” in the Atdabanian. The phyla that he lists in Fig. 2.6 as “explosively” appearing in the Atdabanian stages all actually appeared much earlier—or they are soft-bodied phyla from the Chinese Chengjiang fauna, whose first appearance artificially inflates the count. Meyer deliberately and dishonestly distorts the story by implying that these soft-bodied animals appeared all at once, when he knows that this is an artifact of preservation. It’s just an accident that there are no extraordinary soft-bodied faunas preserved before Chengjiang, so we simply have no fossils demonstrating their true first appearance, which occurred much earlier based on molecular evidence.

The details of the Cambrian diversification event, showing how different groups appear in different stages of the Precambrian and Cambrian. Meyer completely ignores the existence of the first two stages of the Cambrian, falsely giving the impression that it is abrupt and rapid.

Meyer’s distorted and false view of conflating the entire Early Cambrian (543-515 m.y. ago) as consisting of only the third stage of the Early Cambrian (520-515 m.y. ago) creates a fundamental lie that falsifies everything else he says in the ensuing chapters. He even attacks me (p. 73) by claiming that during our 2009 debate, it was I who was improperly redefining the Cambrian! Even a cursory glance at anyrecent paleontology book on the topic, or even the Wikipedia site for “Cambrian explosion”, shows that it is Meyer who has cherry-picked and distorted the record, completely ignoring the 23 million years of the first two stages of the Cambrian because their existence shoots down his entire false interpretation of the fossil record. Sorry, Steve, but you don’t get to contradict every paleontologist in the world, ignore the evidence from the first two stages of the Cambrian, and redefine the Early Cambrian as the just the Atdabanian Stage just to fit your fairy tale!

Even if we grant the premise that a lot of phyla appear in the Atdabanian (solely because there are no soft-bodied faunas older than Chengjiang in the earliest Cambrian), Meyer claims the 5-6 million years of the Atdabanian are too fast for evolution to produce all the phyla of animals. Wrong again! Lieberman (2003) showed that rates of evolution during the “Cambrian explosion” are typical of any adaptive radiation in life’s history, whether you look at the Paleocene diversification of the mammals after the non-avian dinosaurs vanished, or even the diversification of humans from their common ancestor with apes 6 m.y. ago. As distinguished Harvard paleontologist Andrew Knoll put it in his 2003 book, Life on a Young Planet:

Was there really a Cambrian Explosion? Some have treated the issue as semantic—anything that plays out over tens of millions of years cannot be “explosive,” and if the Cambrian animals didn’t “explode,” perhaps they did nothing at all out of the ordinary. Cambrian evolution was certainly not cartoonishly fast … Do we need to posit some unique but poorly understood evolutionary process to explain the emergence of modern animals? I don’t think so. The Cambrian Period contains plenty of time to accomplish what the Proterozoic didn’t without invoking processes unknown to population geneticists—20 million years is a long time for organisms that produce a new generation every year or two. (Knoll, 2003, p. 193)

(It’s interesting that Meyer talks about millions of years like an ordinary geologist might. I’ll bet his Young-Earth Creationist readers, who refuse to concede the earth is older than 10,000 years old, are not to happy with him for this. This might explain why the book, which was artificially pushed up the best-seller list by a huge creationist publicity effort before it was published, has now dropped out of the best-seller list like a stone, once people see it’s not supporting Young-Earth Creationism).

The mistakes and deliberate misunderstandings and misinterpretations go on and on, page after page. Meyer takes the normal scientific debates about the early conflicts about the molecular vs. morphological trees of life as evidence scientists know nothing, completely ignoring the recent consensus between these data sets. Like all creationists, he completely misinterprets the Eldredge and Gould punctuated equilibrium model and claims that they are arguing that evolution doesn’t occur—when both Gould and Eldredge have clearly explained many times (which he never cites) why their ideas are compatible with Neo-Darwinism andnot any kind of support for any form of creationism. He repeats many of the other classic creationist myths, all long debunked, including the post hoc argument from probability (you can’t make the argument that something is unlikely after the fact), knowing that his math-phobic audience is easily bamboozled by the misuse of big numbers. He wastes a full chapter on the empty concept of “information” as the ID creationists define it. He butchers the subject of systematic biology, using the normal debate between competing hypotheses to argue that scientists can’t make up their minds—when that is the ordinary way in which scientific questions are argued until consensus has been reached. He confuses crown-groups with stem-groups, botches the arguments about recognition of ancestors in the fossil record, and can’t tell a cladogram from a family tree. He blunders through the fields of epigenetics and evo-devo and genetic drift as if they completely falsified Neo-Darwinism, rather than as scientists view them, as supplements to our understanding of it. (Even if they did somehow shoot down some aspects of Neo-Darwinism, they are providing additional possible mechanisms for evolution, something he supposedly does not believe in!). In short, he runs the full gamut of topics in modern evolutionary biology, managing to distort or confuse every one of them, and only demonstrating that he is completely incapable of understanding these topics.

In several places in the book, he shows his pictures of the Cambrian sections in China, or talks in the final chapter about visiting the Burgess Shale in Canada (aMiddle Cambrian locality, millions of years after the “Cambrian explosion” was long over), as if to establish his street-cred that he at least got away from his office and computer once in a while. Visiting these famous places like a tourist doesn’t qualify you to write a guidebook of the complexity of the fossils that were recovered there. If he had actually done the hard work of learning about paleontology and doing the research in the field himself (as real scientists have), we might take him seriously. As it is, this book only demonstrates that Meyer can completely misunderstand, misinterpret and misread subjects like paleontology just as badly as he botched his interpretation of molecular biology. (For a good account by real paleontologists who know what they’re doing, see the excellent recent book by Valentine and Erwin, 2013, which gives an accurate view of the “Cambrian diversification”).

Finally, one might wonder: what’s all the fuss about the “Cambrian explosion”? Why should it matter whether evolution was fast or slow during the third stage of the Cambrian? Some scientists might find this puzzling, but you must understand the minds of creationists. They operate by a “god of the gaps” argument: anything that is currently not easily explained by science is automatically attributed to supernatural causes. Even though ID creationists say that this supernatural designer could be any deity or even extraterrestrials, it is well documented that they are thinking of the Judeo-Christian god when they point to the complexity and “design” of life. They argue that if scientists haven’t completely explained every possible event of the Early Cambrian, science has failed and we must consider supernatural causes.

Of course, this is a lie. For one thing, Meyer’s description of the “Cambrian explosion” is distorted and false, since he deliberately ignores the events of the first two stages of the Cambrian. Secondly, this “god of the gaps” approach is guaranteed to fail, because scientists have explained most of the events of the Early Cambrian and find nothing out of the ordinary that defies scientific explanation. Only a few details remain to be worked out. As our fossil record of that time interval improves and we understand it even better, there will be nothing left for the creationists to point to that might require supernatural intervention. This is a losing strategy for them in every possible way.

In short, Meyer has shown that his first disastrous book was not a fluke: he is capable of going into any field in which he has no training or research experience and botching it just as badly as he did molecular biology. As I’ve written before, if you are a complete amateur and don’t understand a subject, don’t demonstrate the Dunning-Kruger effect by writing a book about it and proving your ignorance to everyone else! Some people with creationist leanings or little understanding of paleontology might find this long-winded, confusingly written book convincing, but anyone with a decent background in paleontology can easily see through his distortions and deliberate misunderstandings and misinterpretations. Even though Amazon.com persists in listing this book in their “Paleontology” subsection, I’ve seen a number of bookstores already which have it properly placed in their “Religion” section—or even more appropriately, in “Fiction.”

Postscript: When I first wrote this book review, I posted it on the book’s Amazon.com site. Naturally, it got a huge reaction out of the creationists, and there was a string over over 1900 comments on my review. Surprisingly, the scientists and paleontologists managed to overwhelm the usual comments of the creationists, and about 70% of the commenters marked my harsh review as “helpful”. The creationist comments were mostly personal attacks on me, or claims that I didn’t read the book, not substantive comments about my points about Meyer’s ignorance of paleontology.

Unsurprisingly, it also got a harsh attack from the Discovery Institute in Seattle, Meyer’s home institution. Their spokesman Casey Luskin (a lawyer, not a paleontologist) criticized my review by using all the classic creationist tactics. Mostly he quote-mines Erwin and Valentine’s new book to make it appear that these distinguished paleontologists are creationists! (When I pointed this out to my good friend Doug Erwin, he found it laughable and made it clear to me that in no way does his book support creationism or Meyer’s misinterpretations—not that Luskin would care if Erwin himself wrote a detailed refutation of every bit of misquotation the DI post used). The rest of Luskin’s ridiculous post claims I didn’t read the book, or really read the chapters where Meyer made specific arguments. (I sure did read them—but no matter how many times you read it, Meyer’s arguments and statements are completely wrong, and Meyer does not understand the key issues but grossly misinterprets them). In short, it’s the usual pack of lies and distortions and quote-mines and diversionary tactics designed to mislead the casual reader who does not understand what I wrote, not addressing the key points of contention in my review. In no place does Luskin acknowledge or even mention the central point of this review: that Meyer has deliberately and dishonestly ignored the first two stages of the Cambrian to give the false impression that it was inexplicably rapid.

Finally, I should note an interesting phenomenon. The creationist community gave the book a huge buildup in their circles, and got their acolytes to pre-order the book in huge numbers, so it was #7 on the New York Times Best Seller List when it was released. Since its release, however, it has plummeted in sales, probably because once the Young-Earth Creationists read it, they’ll realize it is full of ideas they don’t support, like “millions of years.” I watched its sales ranking on Amazon.com go from near the top, to (currently) around #11,000 or lower on the ranking of best sellers—in just over a month! The most satisfying thing, however, is that initially Amazon.com put it in their “Paleontology” category. But just a week ago, they removed it and moved it to “Religion & Science.” Apparently, the huge negative backlash from REAL paleontologists made them reassess it. Now if they could only move it over to “Fiction”, where it truly belongs…

References

- Erwin, D., and J.W. Valentine. 2013. The Cambrian Explosion: The Construction of Biodiversity. Roberts and Company, Publishers, New York.

- Knoll, A.H. 2003. Life on a Young Planet: The First Three Billion Years of Life on Earth. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

- Lieberman, B.S. 2003. Taking the pulse of the Cambrian radiation. Integrative and Comparative Biology 43:229-237.

- Prothero, D.R. 2007. Evolution: What the Fossils Say and Why it Matters. Columbia University Press, New York.

No comments:

Post a Comment